Tag: Schedule

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23777%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(149.2%20371.2%20404.8)%20scale(463.75391%20392.10764)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(96.5%2064.7%20169.6)%20scale(433.95662%20252.30266)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-161.59873%20-163.56151%20875.18749%20-864.68501%201383.9%201123)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23020202%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(172.3124%20-127.54088%20617.9838%20834.91878%201501.7%20170.7)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

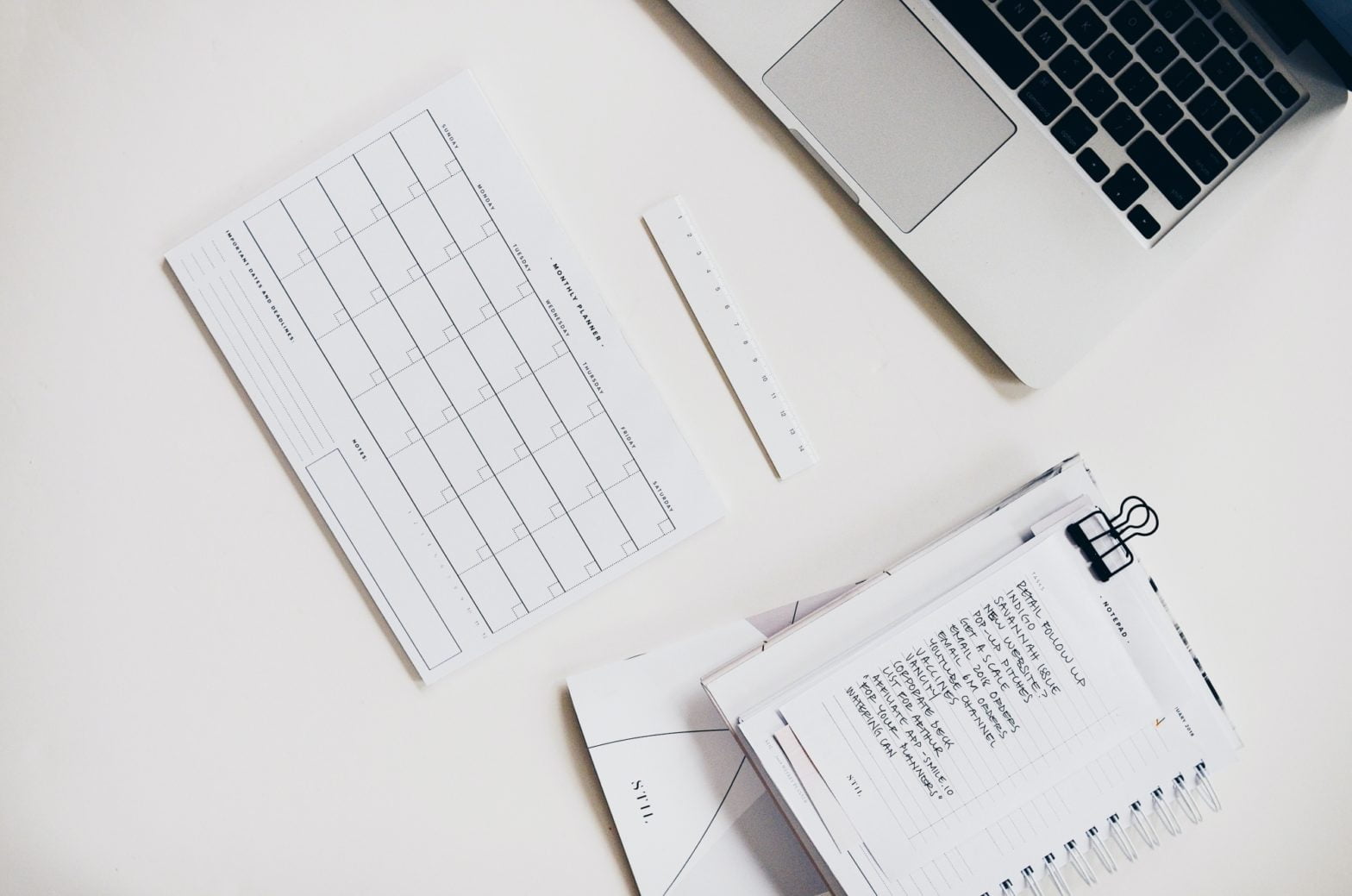

You Need to Know What You Want to Accomplish in 2024

What do you want to accomplish in the next year? Intentionally planning with these 5 steps will help you make the most of it.

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(3%203)%20scale(6.125)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23878787%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(107.6%20-1.5%20121.1)%20scale(50.76899%2039.79803)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23868686%22%20cy%3D%22166%22%20rx%3D%2229%22%20ry%3D%2229%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23878787%22%20d%3D%22M271%2025.5v-30l-43.7-10.2%208.6%2038.7z%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23c4c4c4%22%20d%3D%22M249-16L37%20172-16%202z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

How to Budget Your Time If It’s Irregular

Having an irregular schedule doesn’t mean you can’t budget your time. It just means you need to focus on the commitments that are most important.

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(3%203)%20scale(6.125)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23878787%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(107.6%20-1.5%20121.1)%20scale(50.76899%2039.79803)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23868686%22%20cy%3D%22166%22%20rx%3D%2229%22%20ry%3D%2229%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23878787%22%20d%3D%22M271%2025.5v-30l-43.7-10.2%208.6%2038.7z%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23c4c4c4%22%20d%3D%22M249-16L37%20172-16%202z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

How to Best Budget Your Time When It’s Regular

Time blocking is a great way of budgeting time because it shows when you’ve spent time and whether you’ve spent it on what’s important.

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23282828%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-12.8%20757.9%20-6621.5)%20scale(499.60303%20250.65132)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%232b2b2b%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(2.08185%2098.21123%20-262.4832%205.56405%201412.4%2028)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23aaa%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-320.78065%20-153.46188%2065.61654%20-137.15795%201080.7%20202.4)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23ededed%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M1663%20664.6L27.5-95-95%201099.4z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

You Need to Budget Your Time to Avoid Guilt and Shame

You need to budget your time to avoid having priorities assigned to it by social pressure that aren’t consistent with your vocation.

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23282828%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-12.8%20757.9%20-6621.5)%20scale(499.60303%20250.65132)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%232b2b2b%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(2.08185%2098.21123%20-262.4832%205.56405%201412.4%2028)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23aaa%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-320.78065%20-153.46188%2065.61654%20-137.15795%201080.7%20202.4)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23ededed%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M1663%20664.6L27.5-95-95%201099.4z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

You Need to Budget Your Time to Avoid Schedule Crises

Budgeting your time can help put you in a better position to avoid additional time and energy spent managing schedule crises.

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23282828%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-12.8%20757.9%20-6621.5)%20scale(499.60303%20250.65132)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%232b2b2b%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(2.08185%2098.21123%20-262.4832%205.56405%201412.4%2028)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23aaa%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-320.78065%20-153.46188%2065.61654%20-137.15795%201080.7%20202.4)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23ededed%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M1663%20664.6L27.5-95-95%201099.4z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

You Need to Budget Your Time to Get the Most Out of It

You need to budget your time in order to get the most out of it not only by doing more things but also—and more importantly—by doing more important things.