Blog

Why You Might Want to Send Secure Email

Between recipients, email isn’t always secure. To avoid countless hours cleaning up after a message that got into mischievous hands, consider secure email.

%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(4%200%200%204%202%202)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(.33046%2037.86647%20-254.99026%202.22527%20114%20235)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23efc7c9%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(33.64498%2040.71163%20-98.75335%2081.61193%2065.8%2083.3)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23df4628%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-42.70236%20-2.76144%206.2482%20-96.62092%20129.2%20135.6)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23c8cbd3%22%20cx%3D%22214%22%20cy%3D%22100%22%20rx%3D%2252%22%20ry%3D%2266%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

How to Synchronize Your Zotero Profile—without a Database Catastrophe

You can’t safely synchronize your Zotero database other than with Zotero. But you can synchronize your other profile data if you configure things carefully.

%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(2.5%200%200%202.5%201.3%201.3)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(83.785%2038.00656%20-18.361%2040.4766%20129.5%2040.2)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20cx%3D%2214%22%20cy%3D%2226%22%20rx%3D%22182%22%20ry%3D%2231%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23d6d6d6%22%20cx%3D%2267%22%20cy%3D%22127%22%20rx%3D%2277%22%20ry%3D%2277%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23d6d6d6%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(99.77046%20-223.03965%2039.58754%2017.70836%20231.9%20117.4)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

You Need to Know What’s Essential

There’s no one-size-fits all solution to avoiding overwhelm. But a central question you need to ask is “What’s essential?”

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(84.4%204.4%20204.3)%20scale(863.37799%20247.15106)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-25%201565.6%20-3293)%20scale(170.32218%20278.19014)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(244.63712%20771.81957%20-430.854%20136.56415%20950.9%20567.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M1249%20177l-80.3-198.7L1538-171l80.2%20199z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

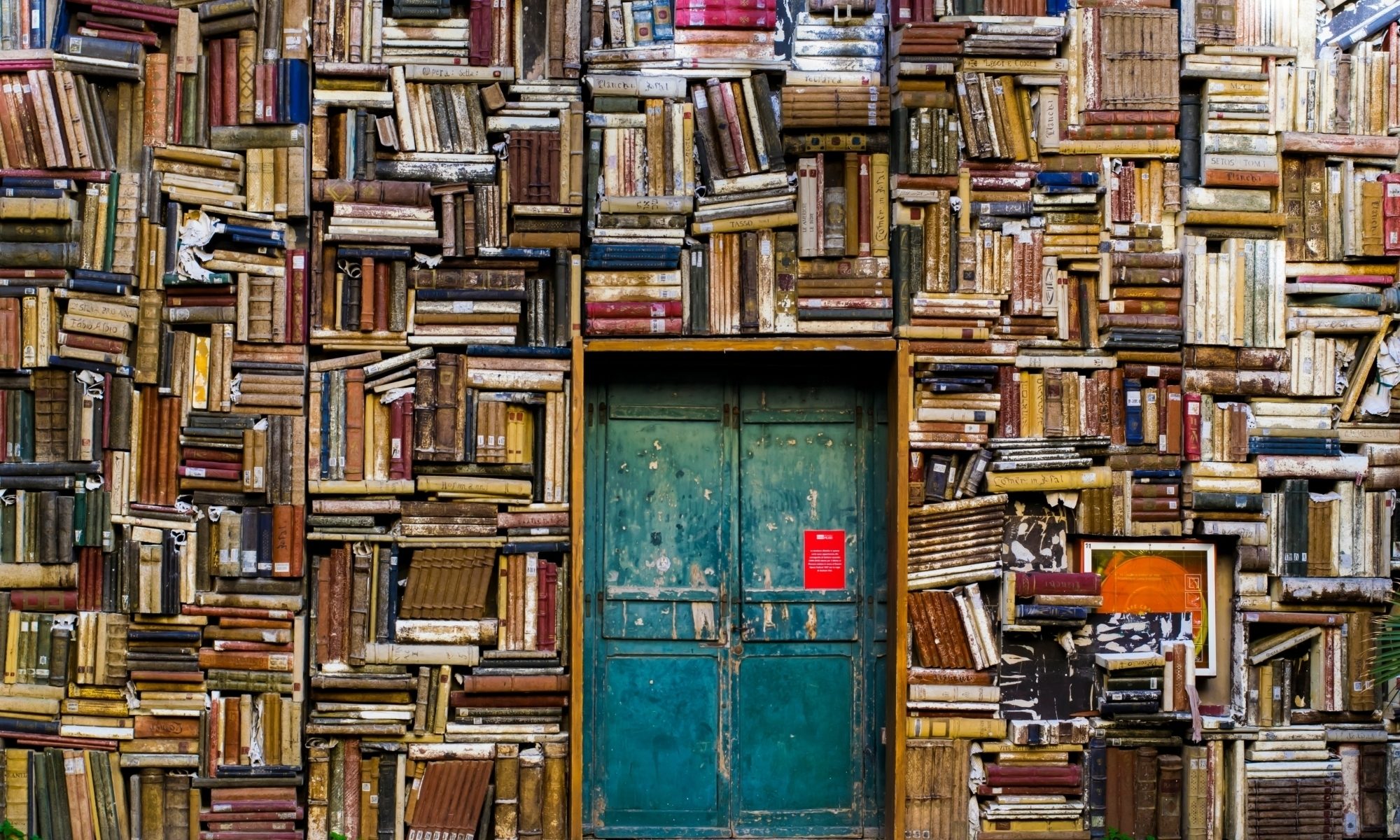

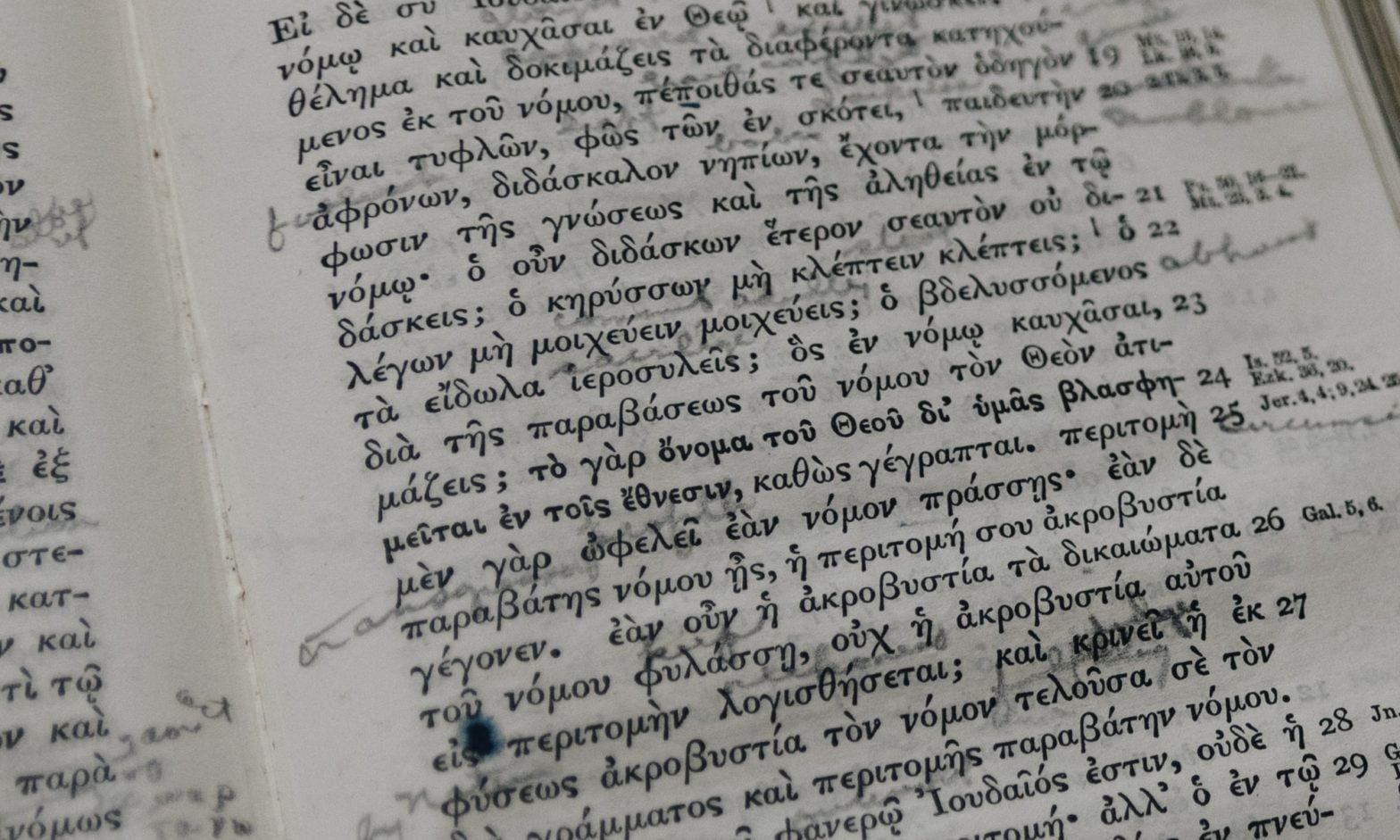

12 Reasons You Need to Read Your Bible

Critical biblical scholarship is irreplaceable. But even when you do this, there are 12 reasons you still need to read your Bible.

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%232e3d38%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-263.8182%20-35.33463%2082.4593%20-615.66412%201323.1%2029)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23434c49%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(218.00913%20-50.29922%2069.33289%20300.50572%201502.4%20870.4)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dcdadb%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-299.35435%20642.00822%20-518.7978%20-241.90403%20487.1%20848.8)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23495c59%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(415.371%20-121.07388%2046.27797%20158.76692%20140.7%2056)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

Why You Need to Maintain a Waiting-for List

The more complex life gets, the more useful a waiting-for list becomes. This simple tool, well used, will more than pay back your time in maintaining it.