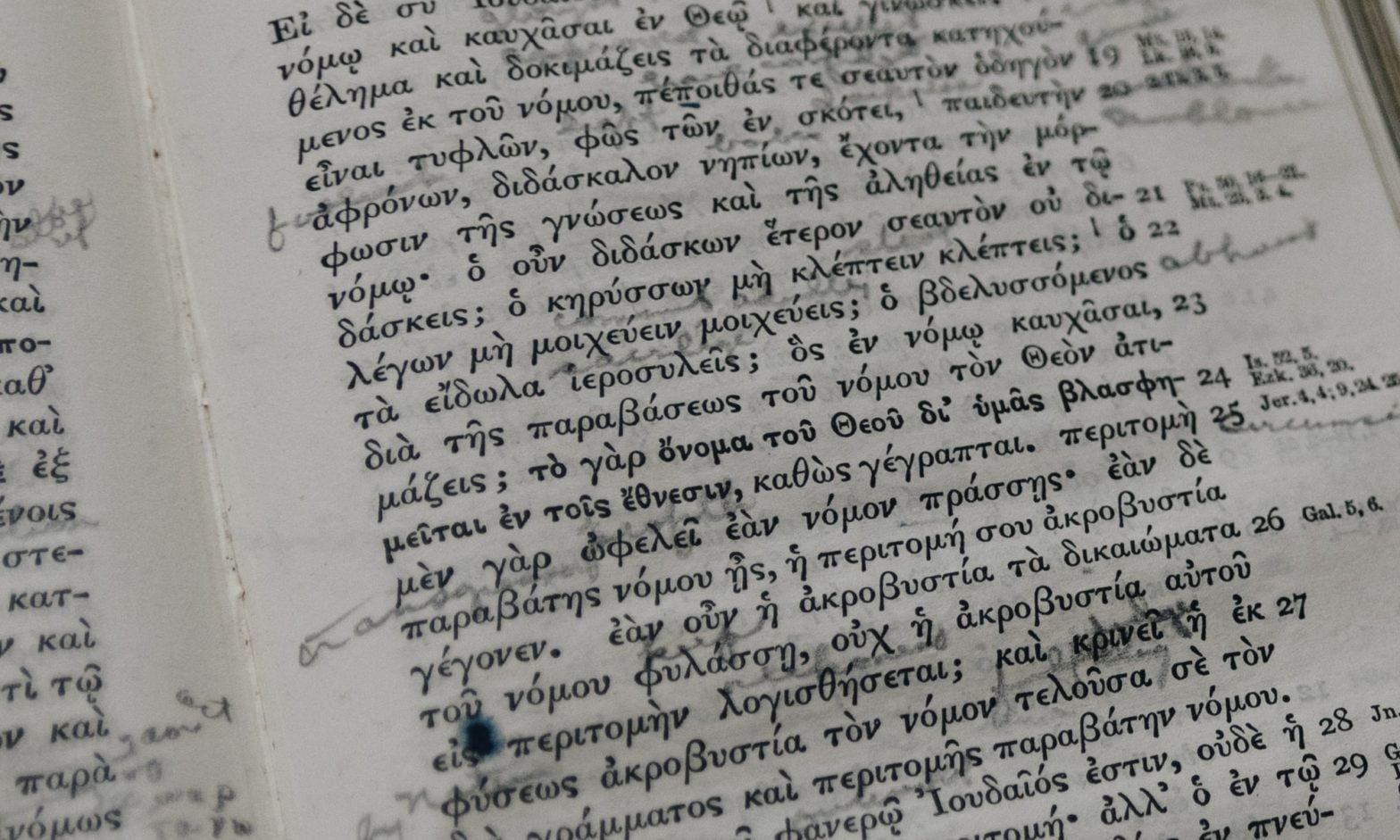

Tag: Textual Criticism

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(3%203)%20scale(6.125)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dadada%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-6.92116%20-24.68636%2029.02162%20-8.1366%20204.6%20145)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%239f9f9f%22%20d%3D%22M-12-16l282%20119-223%2058z%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23c2c2c2%22%20d%3D%22M173.8%20127.8l23.2-2.5%2031.6%2015.5-50.9%2020.2z%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%239f9f9f%22%20cx%3D%22244%22%20cy%3D%22130%22%20rx%3D%2213%22%20ry%3D%22255%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

How to Find Your Way around the Aleppo Codex

Printed texts have their virtues. But sometimes you need to look at a manuscript. Here’s how to find your way around the Aleppo Codex.

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(84.4%204.4%20204.3)%20scale(863.37799%20247.15106)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-25%201565.6%20-3293)%20scale(170.32218%20278.19014)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(244.63712%20771.81957%20-430.854%20136.56415%20950.9%20567.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M1249%20177l-80.3-198.7L1538-171l80.2%20199z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

How to Avoid Missing Manuscript Images

In INTF’s database, sometimes a transcription isn’t available or a manuscript image is harder to read. In these cases, check external image repositories.

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(84.4%204.4%20204.3)%20scale(863.37799%20247.15106)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-25%201565.6%20-3293)%20scale(170.32218%20278.19014)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(244.63712%20771.81957%20-430.854%20136.56415%20950.9%20567.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M1249%20177l-80.3-198.7L1538-171l80.2%20199z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

How to Quickly See Manuscript Information in INTF’s Database

With the document ID handy, INTF’s Liste search makes it quite easy to see additional information about that manuscript—and possibly the manuscript itself.

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(84.4%204.4%20204.3)%20scale(863.37799%20247.15106)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-25%201565.6%20-3293)%20scale(170.32218%20278.19014)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(244.63712%20771.81957%20-430.854%20136.56415%20950.9%20567.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M1249%20177l-80.3-198.7L1538-171l80.2%20199z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

What You Need to Know to Use INTF’s Document ID System

Once you understand INTF’s system, you can call up any manuscript in the database. For Greek New Testament witnesses, the document ID is a 5-digit sequence.

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(84.4%204.4%20204.3)%20scale(863.37799%20247.15106)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-25%201565.6%20-3293)%20scale(170.32218%20278.19014)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(244.63712%20771.81957%20-430.854%20136.56415%20950.9%20567.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M1249%20177l-80.3-198.7L1538-171l80.2%20199z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

What Do You Do When Your Critical Apparatus Is Confusing?

A modern Greek New Testament’s critical apparatus holds a wealth of information. When you’re uncertain what the apparatus means, consult the manuscripts.

Daily Gleanings: Textual Criticism (2 January 2020)

Now available from Brill is Donald Parry’s treatment of the Dead Sea Isaiah scrolls and their variants.