Tag: Second Temple Judaism

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(3%203)%20scale(6.125)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23c3e1f8%22%20cx%3D%22216%22%20cy%3D%22100%22%20rx%3D%2274%22%20ry%3D%2286%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%239c470c%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(38.48224%203.04405%20-20.10837%20254.20593%2030.6%2077.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dc8f55%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-38.79691%20-6.14483%2019.1884%20-121.15074%2095.7%2067.1)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23733a0d%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(164.2%20-9%2079.5)%20scale(26.96007%2055.38367)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

Research on (Re)writing Prophets in the Corinthian Correspondence

If hermeneutics of “rewritten Bible” are highlighted, it’s easier to compare these texts and their hermeneutics with Paul’s interpretive work.

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(1.2%201.2)%20scale(2.42969)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23d29a00%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(1.59016%2070.07222%20-167.1885%203.79404%2074.5%20202.4)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(166.01299%201.73855%20-.77486%2073.9908%2085.9%2056)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20cx%3D%2283%22%20cy%3D%2252%22%20rx%3D%22171%22%20ry%3D%2265%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dab800%22%20cx%3D%2294%22%20cy%3D%22206%22%20rx%3D%22171%22%20ry%3D%2258%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

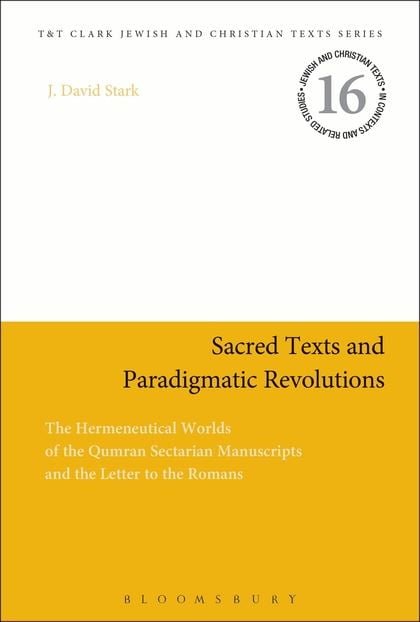

Confused or Intrigued with Second Temple Hermeneutics?

“Sacred Texts and Paradigmatic Revolutions” illustrates how modern readers can work to recover Second Temple interpretive contexts.

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(3%203)%20scale(6.125)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23fff%22%20cx%3D%22238%22%20cy%3D%2241%22%20rx%3D%2228%22%20ry%3D%22168%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%236a6c64%22%20d%3D%22M-16-16l209%2047-2%20141z%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%236c6c6d%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(20.2%20-400%20181)%20scale(83.22913%2029.00015)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23f4f4f4%22%20cx%3D%22249%22%20cy%3D%2280%22%20rx%3D%2215%22%20ry%3D%22176%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

Audience and Predestination in the Letter to the Romans

A perennial question in the interpretation of Paul’s letter to the Romans is what testimony the letter bears on the issue of predestination.1 Especially in the last few decades, the identity of the letter’s implied audience has also become more of a live question. Discussing These Difficulties I recently had the opportunity to sit down…

Daily Gleanings: Community Rule (31 December 2019)

Sarianna Metso’s edition of the Community Rule addresses all surviving witnesses for the Rule and includes a critical apparatus.

Daily Gleanings: New Publications (24 July 2019)

In the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 62.2 (353–69), Greg Goswell contemplates “Reading Romans after the Book of Acts.” According to the abstract, The Acts-Romans sequence, such as found in the Latin manuscript tradition and familiar to readers of the English Bible, is hermeneutically significant and fruitful. Early readers had good reason to place…

UC Classics podcast

The University of Cincinnati’s Department of Classics has a podcast with several noteworthy episodes, including an interview with Jodi Magness and a whole series on Qumran and Judean Desert texts. HT: AWOL