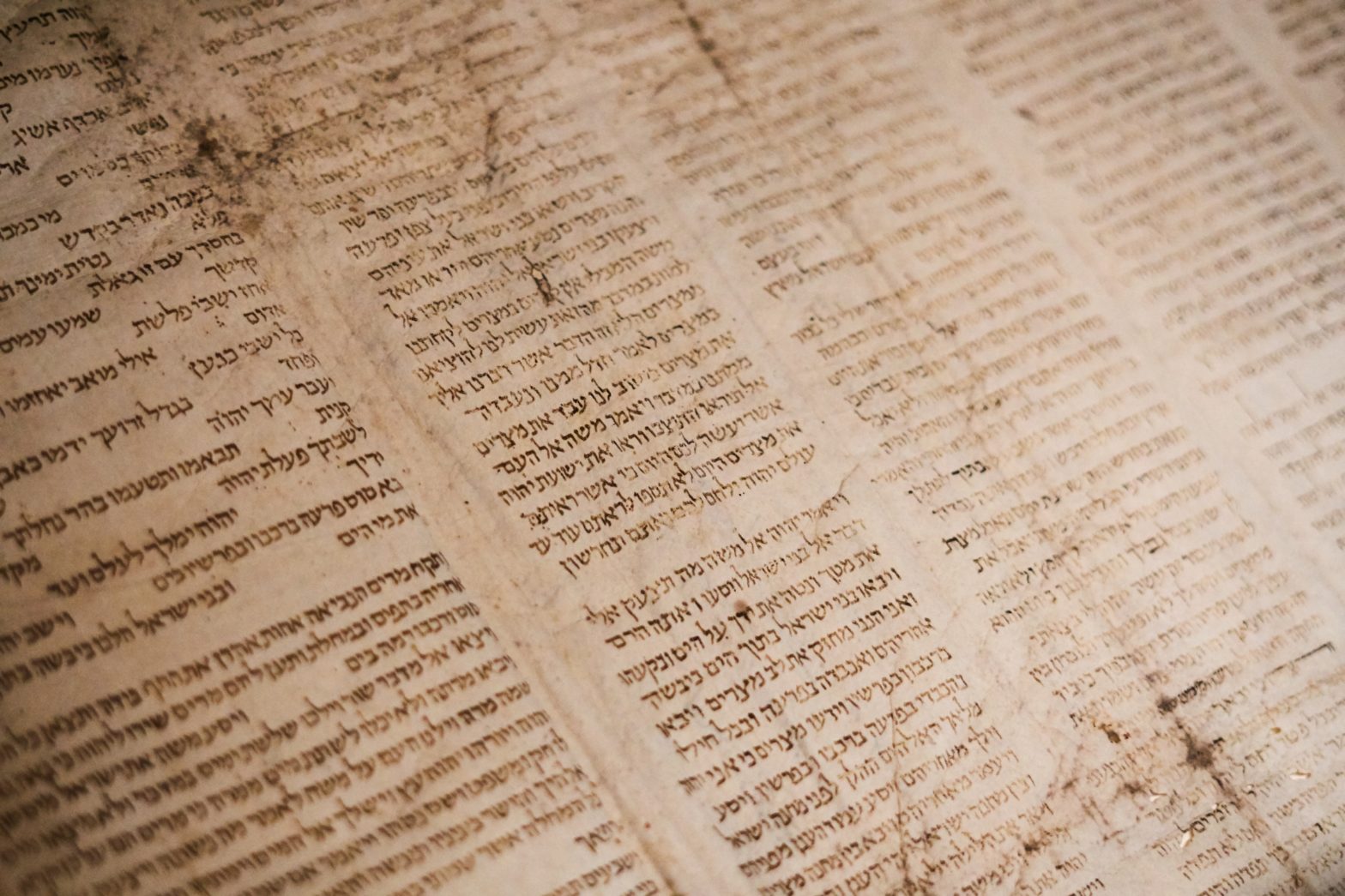

Tag: Masorah

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(3%203)%20scale(6.125)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23c3e1f8%22%20cx%3D%22216%22%20cy%3D%22100%22%20rx%3D%2274%22%20ry%3D%2286%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%239c470c%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(38.48224%203.04405%20-20.10837%20254.20593%2030.6%2077.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dc8f55%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-38.79691%20-6.14483%2019.1884%20-121.15074%2095.7%2067.1)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23733a0d%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(164.2%20-9%2079.5)%20scale(26.96007%2055.38367)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

Okhlah we-Okhlah: What It Is, Why It’s Important, and How to Get It

Okhlah we-Okhlah is a medieval compilation of information about the Hebrew Bible. Here are the basics about why it’s important and how to access it.

Phillips on a textual relative of the Leningrad Codex

The latest issue of the Tyndale Bulletin carries Kim Phillips’s essay, “A New Codex from the Scribe behind the Leningrad Codex: L17.” According to the abstract, Samuel b. Jacob was the scribe responsible for the production of the so-called Leningrad Codex (Firkowich B19a), currently our earliest complete Masoretic Bible codex. This article demonstrates that another codex from the Firkowich Collection,…

Review of Biblical Literature Newsletter (May 7, 2015)

The latest reviews from the Review of Biblical Literature include: Markus Bockmuehl and Guy G. Stroumsa, eds., Paradise in Antiquity: Jewish and Christian Views, reviewed by Pieter G. R. de Villiers Tony Burke, ed., Ancient Gospel or Modern Forgery?: The Secret Gospel of Mark in Debate: Proceedings from the 2011 York University Christian Apocrypha Symposium, reviewed by…