Tag: Hebrew Bible

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(3%203)%20scale(6.125)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dadada%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-6.92116%20-24.68636%2029.02162%20-8.1366%20204.6%20145)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%239f9f9f%22%20d%3D%22M-12-16l282%20119-223%2058z%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23c2c2c2%22%20d%3D%22M173.8%20127.8l23.2-2.5%2031.6%2015.5-50.9%2020.2z%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%239f9f9f%22%20cx%3D%22244%22%20cy%3D%22130%22%20rx%3D%2213%22%20ry%3D%22255%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

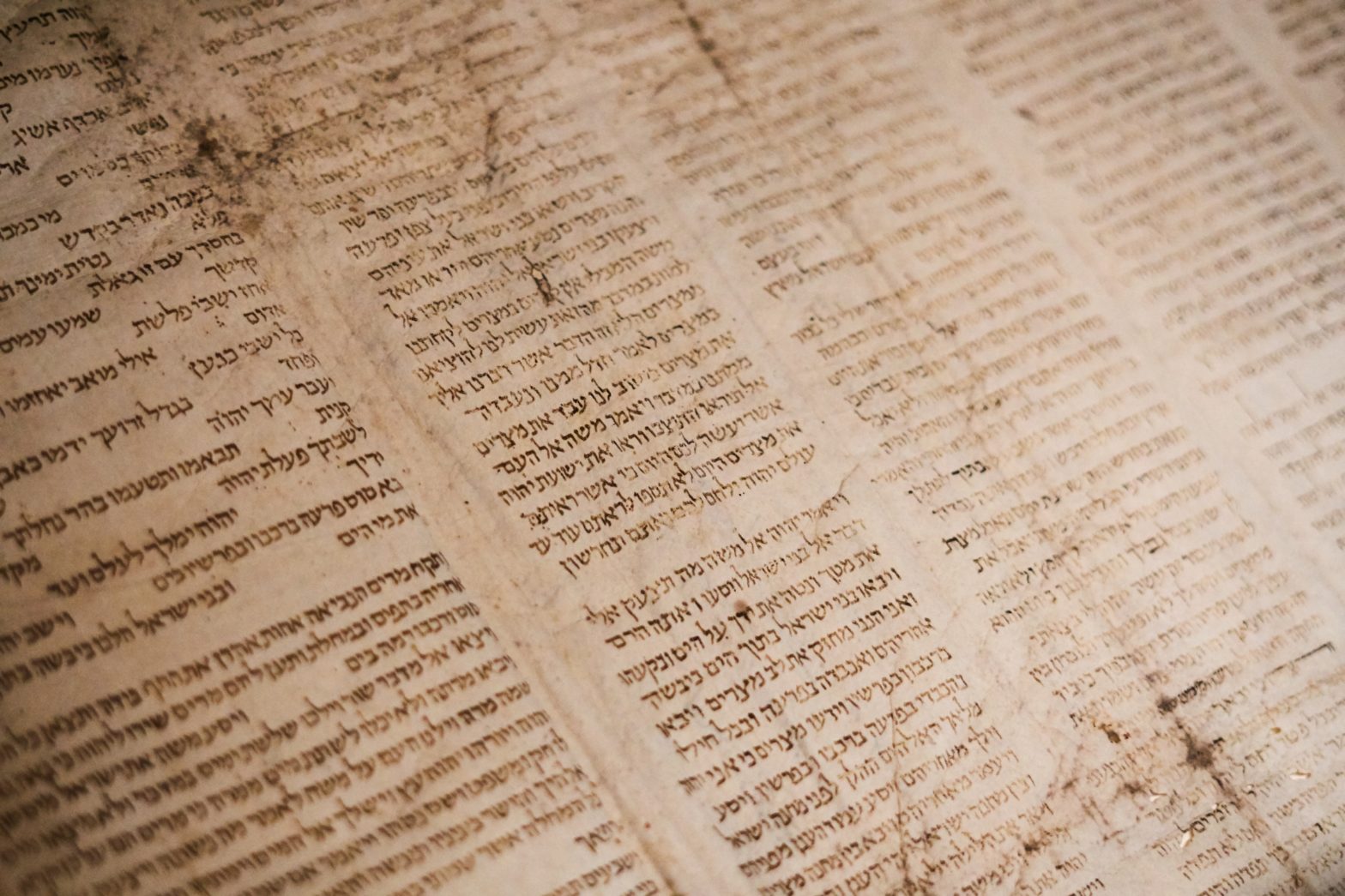

How to Find Your Way around the Aleppo Codex

Printed texts have their virtues. But sometimes you need to look at a manuscript. Here’s how to find your way around the Aleppo Codex.

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(3%203)%20scale(6.125)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23c3e1f8%22%20cx%3D%22216%22%20cy%3D%22100%22%20rx%3D%2274%22%20ry%3D%2286%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%239c470c%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(38.48224%203.04405%20-20.10837%20254.20593%2030.6%2077.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23dc8f55%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-38.79691%20-6.14483%2019.1884%20-121.15074%2095.7%2067.1)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23733a0d%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(164.2%20-9%2079.5)%20scale(26.96007%2055.38367)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

Okhlah we-Okhlah: What It Is, Why It’s Important, and How to Get It

Okhlah we-Okhlah is a medieval compilation of information about the Hebrew Bible. Here are the basics about why it’s important and how to access it.

Daily Gleanings: Hebrew Bible (14 October 2019)

Daily Gleanings about Ziony Zevit’s edited volume, “Subtle Citation, Allusion, and Translation in the Hebrew Bible” and Jacques van Ruiten’s review.

Daily Gleanings: Assyrian (3 October 2019)

Daily Gleanings about how to get the 21-volume “Assyrian Dictionary” via open access from the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute.

Daily Gleanings: New Titles from SBL Press (9 July 2019)

New from SBL Press is Marvin Sweeney, ed., Theology of the Hebrew Bible, Volume 1: Methodological Studies. According to the publisher, This volume presents a collection of studies on the methodology for conceiving the theological interpretation of the Hebrew Bible among Jews and Christians as well as the treatment of key issues, such as creation,…

Daily Gleanings (22 May 2019)

Freedom discusses how to use their “block all except” whitelisting feature to block out distractions and interruptions. For more discussion of Freedom, see these prior posts. John Meade surveys ch. 4 of Ronald Hendel and Jan Joosten’s How Old Is the Hebrew Bible? (YUP, 2018) and promises a follow-up post “attempting to engage the authors…