Tag: Biblical Studies

%27%20fill-opacity%3D%27.5%27%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(84.4%204.4%20204.3)%20scale(863.37799%20247.15106)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b5b5b5%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22rotate(-25%201565.6%20-3293)%20scale(170.32218%20278.19014)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(244.63712%20771.81957%20-430.854%20136.56415%20950.9%20567.7)%22%2F%3E%3Cpath%20fill%3D%22%23767676%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%20d%3D%22M1249%20177l-80.3-198.7L1538-171l80.2%20199z%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E)

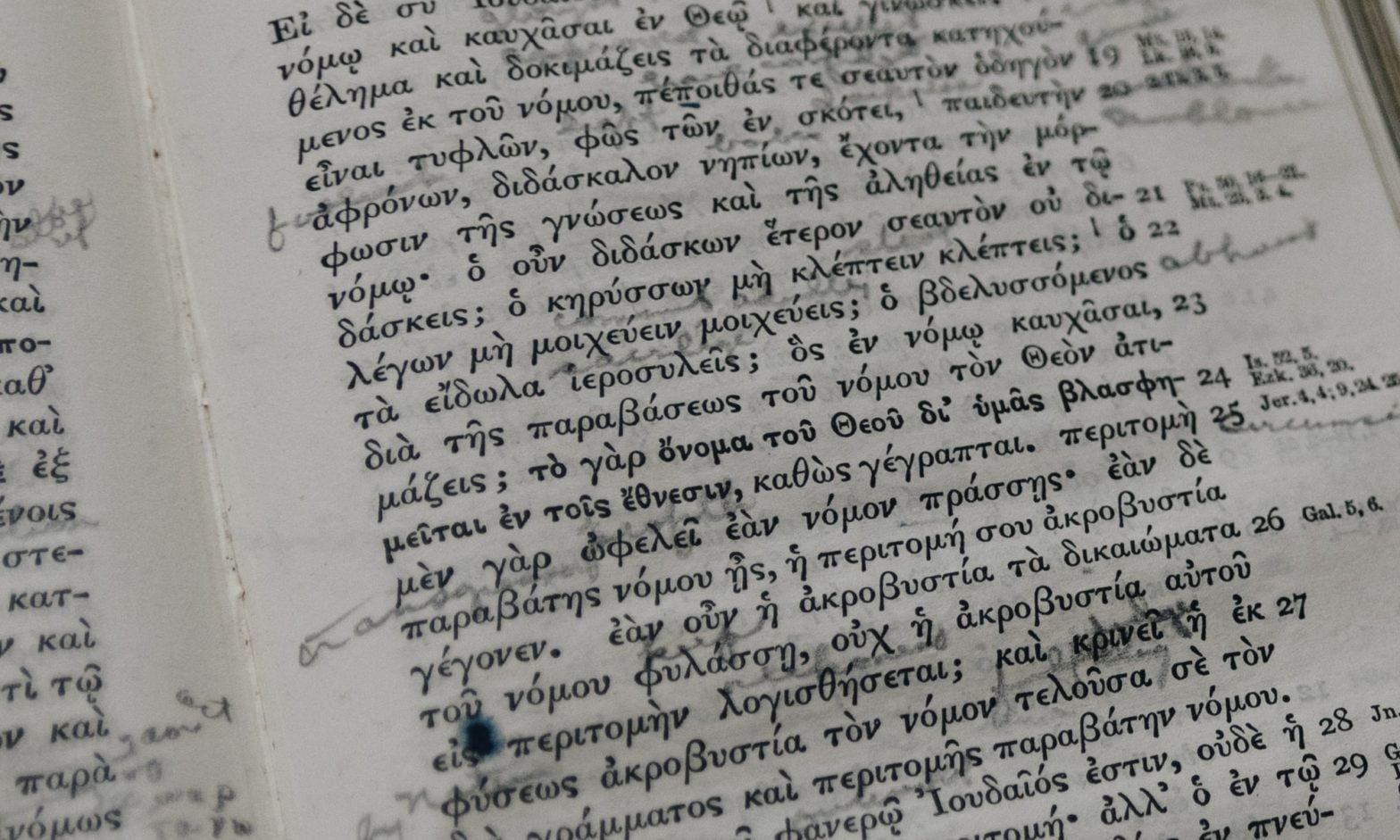

12 Reasons You Need to Read Your Bible

Critical biblical scholarship is irreplaceable. But even when you do this, there are 12 reasons you still need to read your Bible.

Daily Gleanings (30 May 2019)

Roger Pearse discusses the King James Version and provides a good deal of interesting material about the translation principles and procedures behind it. AWOL highlights the open access “Digital Biblical Studies” series: The series aims to publish the latest research at the intersection of Digital Humanities and Biblical Studies, Ancient Judaism, and Early Christianity in…

Theology’s Hermeneutic Interest

H.-G. Gadamer concludes his essay on “The Universality of the Hermeneutical Problem” by commenting on the importance of language, with an interestingly theological turn. Gadamer suggests, The … building up of our own world in language persists whenever we want to say something to each other. The result is the actual relationship of men to…

Free and Trial Biblical Studies Tools

Mark Hoffman has updated his previous list of “free Bible software and trial versions” to include some of the more recent additions in the space, as well as a number of online resources. For further discussion, see also Trial versions of Biblical Studies software, Logos 7 academic basic, and Logos 7 Basic for free.